Emergency Light ,Emergency Lamp,Rechargeable Emergency Light,Led Emergency Light NINGBO JIMING ELECTRIC APPLIANCE CO., LTD. , https://www.jimingemergencylight.com

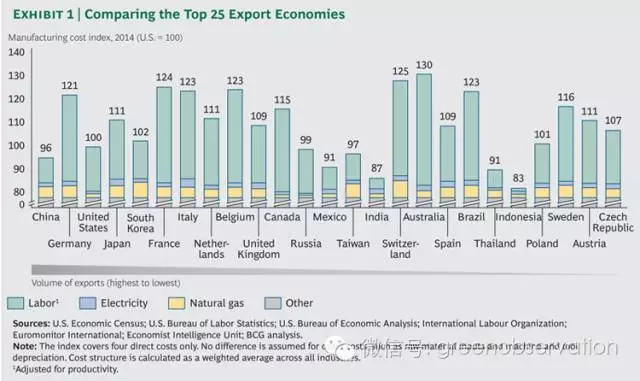

The subtle changes in wages, productivity, energy costs, monetary value, and other factors year after year have quietly and dramatically affected the “global manufacturing cost competitiveness†map. The new map encompasses the intricacies of low-cost economies, high-cost economies, and a large number of economies in between.

The change in relative costs is surprising. Ten years ago, who would have thought that Brazil is now one of the most expensive manufacturing economies or that Mexico’s manufacturing costs will be lower than China’s? Although London is still the world's highest price for living and tourism, the UK has become the lowest cost economy in Western Europe. Manufacturing costs in Russia and Eastern Europe have risen to almost the same level as in the United States (see chart below).

The new Boston Consulting Group's Global Manufacturing Cost Competitiveness Index shows that the relative costs of manufacturing in these economies have changed, prompting many companies to rethink the assumptions of procurement strategies over the past few decades and the location of future development capabilities. To identify and compare changes in relative costs, we analyzed data for 2004 and 2014. This assessment is one of a series of results that we continue to study the global manufacturing economy shift.

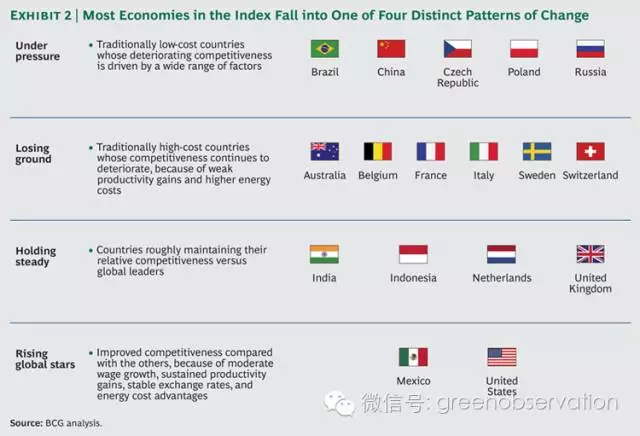

In the process of developing the index, we observed that cost competitiveness has increased in many economies, while other economies have declined relatively. Through this index, we have found four significant patterns of changes in manufacturing cost competitiveness (see figure below).

Faced with pressure: Several economies that have been considered low-cost manufacturing bases in the past have been under pressure from a significant reduction in cost advantages since 2004 due to a combination of factors. For example, it is estimated that the cost advantage of China's factory manufacturing industry has been reduced to less than 5%; Brazil's manufacturing costs are higher than Western Europe; Poland, the Czech Republic and Russia are also relatively weak in cost competitiveness, and their current manufacturing cost levels It is comparable to the United States, only a few percentage points lower than the United Kingdom and Spain.

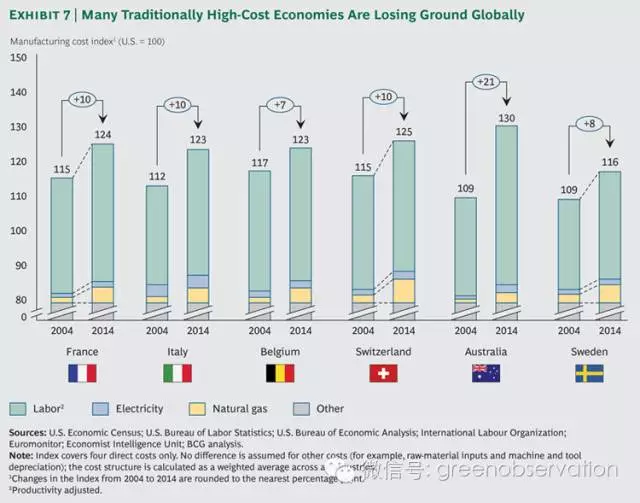

Continue to weaken: In the past decade, the competitiveness of economies with relatively high manufacturing costs has continued to weaken, and their manufacturing costs are 16%-30% higher than those of the United States. The main reasons are low productivity growth and increased energy costs. The economies that continue to weaken their competitiveness include Australia, Belgium, France, Italy, Sweden and Switzerland.

Stable: From 2004 to 2014, many economies remained stable relative to US manufacturing cost competitiveness. In economies such as India and Indonesia, although wages have increased substantially, productivity has increased rapidly and currency depreciation has curbed costs. Compared to the dynamic balance between India and Indonesia, the cost drivers of all our analyses have remained relatively unchanged in the Netherlands and the UK. The cost competitiveness of these four economies makes them likely to be manufacturing leaders in their regions in the future.

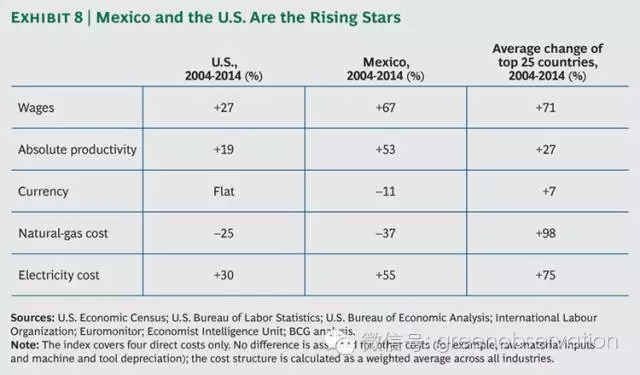

Global Rising: Compared to other top 25 exporting economies, Mexico and the United States have more manufacturing cost structures. These two economies are emerging as new stars in global manufacturing due to low wage growth rates, continued productivity growth, stable exchange rates and huge energy cost advantages. We estimate that the current average manufacturing cost per unit of cost in Mexico is lower than in China. Among the top 10 commodity exporters in the world, except China and South Korea, the manufacturing costs of other economies are higher than those of the United States.

These dynamic changes in the relative costs of manufacturing will prompt companies to reassess their manufacturing locations, leading to a huge shift in the global economy (see chart below). This means that global manufacturing may be more dispersed across regions. Because there are relatively low-cost manufacturing centers in all regions of the world, more consumer goods in Asia, Europe and the Americas will be manufactured closer to the local. In light of these trends, government leaders are increasingly aware of the importance of a stable manufacturing industry to the economy. We hope that this report will encourage policy makers in developed and developing economies to identify their strengths and weaknesses and take action to improve manufacturing competitiveness.

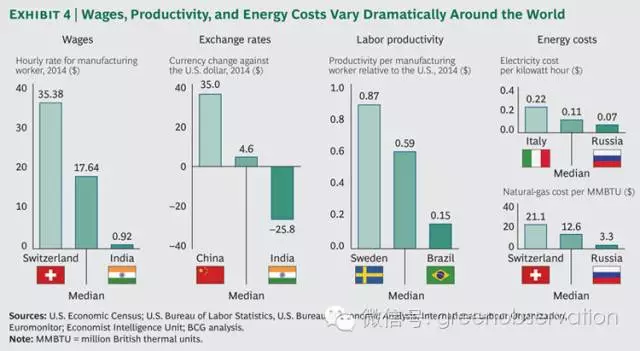

Wages: There is still a huge difference in the hourly wages of manufacturing workers in various economies. But fast-rising wages have greatly weakened the competitive advantage of many major exporting economies. Although manufacturing wages have risen in all of the world's top 25 exporting countries from 2004 to 2014, the average annual wage growth rate of China and Russia has reached 10%-20% for more than 10 years, while others The average annual wage growth rate of the economy is only 2%-3%.

Exchange rate: The impact of changes in the value of a currency on the price of an economy's exports on the international market is two-fold: either more expensive or cheaper. From 2004 to 2014, changes in the value of the currency caused the Indian rupee to depreciate by 26% against the US dollar and the rupee to appreciate by 35% against the renminbi.

Labor productivity: The increase in output of a single manufacturing worker is an increase in productivity. From 2004 to 2014, there has been a huge difference in productivity growth across economies around the world, which explains the most significant changes in the total manufacturing costs of individual economies. From 2004 to 2014, manufacturing productivity in economies such as Mexico, India, and South Korea rose by more than 50%, while manufacturing productivity in Italy and Japan fell. Some economies with low wage growth rates have no obvious advantage in unit labor costs after adjusting for wages with greater productivity.

Energy costs: Since 2004, the price of natural gas in North America has fallen by 25% to 35% due to the large-scale exploitation of shale gas resources. In contrast, natural gas prices in economies such as Poland, Russia, South Korea and Thailand have risen by 100%-200%. This has a huge impact on the use of natural gas as a feedstock for the chemical industry. Similarly, industrial electricity prices in manufacturing economies such as Australia, Brazil and Spain have also risen sharply. As a result, the overall energy costs of many economies outside North America have increased by 50%-200% compared to 2004. This has clearly changed the competitiveness of countries that rely on energy.

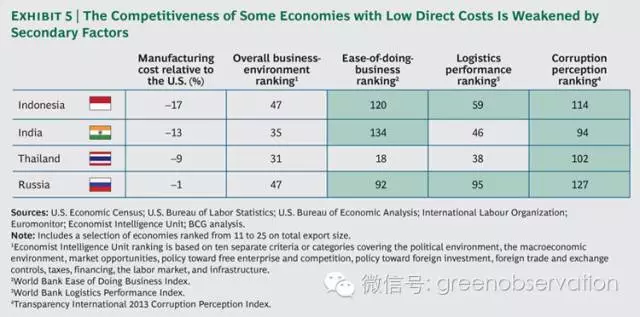

Of course, factors other than wage growth, productivity, exchange rates, and energy costs also largely influence the decision-making of the location of the supply chain. Secondary factors such as logistics costs, ease of doing business, and the presence of corruption can also affect the attractiveness of a location to manufacturing.

We have found in our research that in many economies where direct production costs are attractive, the shortcomings of these secondary factors hinder the growth of manufacturing (see chart below). These secondary factors are closely related to local conditions and even vary widely in different regions of the same economy. Therefore, our cost index model does not calculate these factors. But sensible manufacturing companies must consider these factors when making decisions.

As our research on these macroeconomic trends deepens, we find that the cost shifts in most of the economies in the manufacturing cost competitiveness index show four common patterns: facing pressure, continuing to weaken, maintaining stability, and global stars.

The economies that faced pressure in the past were considered to be low manufacturing costs: Brazil, China, the Czech Republic, Poland and Russia, whose competitive advantage has weakened significantly from 2004 to 2014. The average manufacturing cost of several of these economies is now estimated to be higher than in the United States. Brazil’s manufacturing costs have risen sharply: in 2004 Brazil’s average cost was about 3% lower than in the US and by 2014 it was estimated to be 23% higher than in the US; in 2004, the average cost of Poland and Russia was estimated to be 6% and 13% lower than the US, respectively. Now their average cost is roughly the same as that of the United States; in 2004, the average cost of the Czech Republic was lower than that of the United States by about 3%, and now it is estimated to be higher than the US by 7%; in the same period, China’s manufacturing cost advantage is estimated to fall from 14% to 4 %.

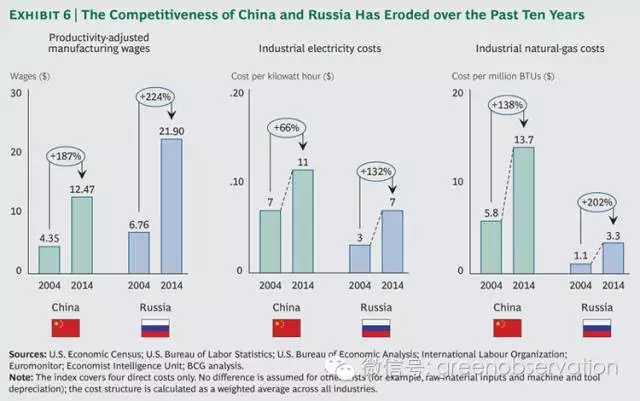

The key factors driving these changes are different. Soaring labor and energy costs have weakened the competitiveness of China and Russia. For example, a decade ago, the average manufacturing wage adjusted for productivity was about $4.35 per hour in China and $6.76 per hour in Russia, compared to $17.54 per hour in the United States. In the past decade, China’s and Russia’s productivity-adjusted average manufacturing wages have tripled, with China reaching $12.47 per hour, Russia reaching $21.90 per hour, and the United States only rising 27% to $22.32 per hour. From 2004 to 2014, the cost of industrial electricity in China and Russia was estimated to rise by 66% and 132%, respectively, while natural gas costs soared by 138% and 202%, respectively (see chart below).

The situation in all aspects of Brazil is also not optimistic. It is worth noting that although Brazil is seen as a major emerging market, even if it was adjusted according to productivity ten years ago, Brazil's manufacturing costs are not much better than those of the United States. The situation is even worse now. From 2004 to 2014, Brazil's manufacturing costs rose by 26% compared to the US. Three-quarters of the increase was caused by high wages and low productivity growth in Brazil.

The wages of Brazilian factory workers have more than doubled in the past decade. Increasing income is a typical indicator of healthy economic development. This decade of steady economic growth has brought millions of Brazilian families from the poor to the middle class. But the increase in productivity in Brazil is not enough to offset the impact of wage increases on manufacturing costs. In fact, from 2004 to 2014, Brazil's total labor productivity increased by only 1%, ranking 19th among the 25 economies in our manufacturing cost competitiveness index.

Previous research by the Boston Consulting Group showed that high wage growth and low productivity growth in Brazil are the main reasons for Brazil's shortage of talent, underinvestment, poor infrastructure and complex and inefficient institutions. The doubling of industrial electricity costs and the nearly 60% increase in natural gas costs have also weakened Brazil's cost competitiveness. Due to the above factors, in our manufacturing cost competitiveness index, Brazil ranks fourth among the “most non-manufacturing cost-competitive economies†with Italy and Belgium, ranking ahead of Australia, Switzerland and France.

Ten years ago, Poland was the most cost-competitive economy in Europe, and it still has an advantage over neighboring economies. For example, Poland's manufacturing costs are 20% lower than in Germany, but it is less than the 23% advantage in 2004. In addition, due to high energy costs and rising wages, Poland lost its advantage over some of the world's most powerful competitors. Poland's productivity increased moderately by about 38% from 2004 to 2014, but the resulting advantages were offset by currency appreciation.

Continue to weaken Ten years ago, the manufacturing costs of most Western European economies were relatively high. Today, some economies in Western Europe are less cost-competitive than before. The average manufacturing cost of Belgium relative to the United States increased by 7%, Sweden by 8%, France, Italy and Switzerland by 10%, and Australia by 21% (see chart below).

Australia: further loss of competitiveness Asia's demand for coal, iron, ore and natural gas has exploded in the past decade, which has greatly contributed to the economic growth of Australia, which is rich in natural resources. Hundreds of billions of Australian dollars have flocked to mining, energy and infrastructure projects and created thousands of high-paying jobs, making Australia still active in the global recession from 2008 to 2009.

Along with the prosperity of Australia's resource industry, it is the decline of manufacturing. The Australian automotive industry has been particularly hard hit. In 2004, Australia's car production was close to 400,000 units, with a total output value of about $9 billion. By 2012, Australian car production has fallen by nearly half. The toughest challenges are still behind, Australia Ford plans to close its engine and car factory in 2016; Toyota Motor and General Motors of the United States also announced that they will close their factories in Australia's Holden Motor Company in 2017. The result will be that these factories (in a broad sense, the Australian automotive industry) will lay off thousands of people.

Although Australia's automotive assembly line is relatively small and the parts factory is difficult to compare with larger, more efficient plants abroad, both GM and Toyota claim that the main reason for closing the plant is Australia's high production costs and strong Australian dollar. Our research confirms the sharp deterioration in Australia's global manufacturing cost competitiveness. Australia has the worst performance among the 25 economies of the Boston Consulting Group's Global Manufacturing Cost Competitiveness Index. Since 2004, Australia's manufacturing cost competitiveness has fallen 21% compared to the US, and its average direct production cost has exceeded that of Germany and the Netherlands. , Belgium and Switzerland. In fact, Australia's competitiveness in every aspect of our index (salary, productivity, energy and currency exchange rates) is further weakening.

Australia's rich resources and infrastructure have led to rising wages and the appreciation of the Australian dollar and capital outflows, which ultimately led to a decline in manufacturing cost competitiveness. Over the past decade, Australian manufacturing wages have risen by 48%, and merchandise exports have led to capital inflows, which have led to a 21% increase in the Australian dollar against the US dollar. At the same time, absolute manufacturing labor productivity fell by 1%.

Australian manufacturing productivity has been weak since 2004, in part because of reduced capital investment. From 2004 to 2012, Australia's average annual actual investment increased by more than 60%, driven by the smelting industry, to reach $430 billion. But manufacturing investment in Australia fell by 6% to just $20.4 billion. Another factor contributing to the decline in manufacturing cost competitiveness in Australia is the low growth in manufacturing productivity, and the situation in this area has been more severe in the past five years. Other reasons for low productivity growth include: labor regulations that lack flexibility; skilled talent programs and labor productivity programs do not receive enough investment.

If other industries in Australia maintain high growth, then the manufacturing downturn may not have much impact. But as the growth of resources and infrastructure industries slows, manufacturing is increasingly becoming an integral part of a diverse economy. The good news is that Australia's other industries (such as the natural resources industry) have grown strongly over the past few years. In addition, Australian companies continue to increase production efficiency. Another inspiring phenomenon in Australia is that while labor-intensive industries such as textiles, clothing and circuit boards are shifting manufacturing abroad, the manufacturing scale of high-value products that require innovation and advanced skills, such as precision medical equipment and consumer electronics, is expanding. . Australia has a certain strength in the manufacture of high-value products, so there are more opportunities.

However, Australia must increase its cost competitiveness by leveraging its potential as a producer of high-value products. This requires companies and governments to commit to investing heavily in technology, skills development, productivity improvement programs and capital equipment in Australia's competitive industries.

To illustrate how weak productivity growth is in these further uncompetitive economies, let's look at the following comparison: From 2004 to 2014, the average production of individual manufacturing workers in Korea increased by 56% during the same period in Italy. The average output of workers is reduced by 6%. The situation in Italy is also in stark contrast to its neighbour, Austria, where the average production of individual manufacturing workers in Austria has increased by about 24% since 2004. Although Austria is the sixth-highest economy in the 25 economies of our competitiveness index, its relative cost competitiveness has not fallen sharply in the past decade, as productivity increases offset wage increases.

In most economies where competitiveness continues to weaken, the less flexible labor market is also responsible for the high labor costs adjusted for productivity. France is another economy that is lagging behind in productivity growth. From 2004 to 2014, the average output of individual workers in France was 14% lower than in the United States. Part of the reason is that France has the most stringent labor regulations in the 25 major exporting economies included in our index. For example, on average, the legal working day does not exceed 7 hours per day. Employers must provide workers with 30 days of paid annual leave. night shift.

Stabilization Four of the 25 exporting countries included in our index (both developing and developed economies) have maintained stable cost competitiveness from 2004 to 2014 with rising global energy costs. They are: India, Indonesia, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. The overall manufacturing cost of each of these economies is higher or lower than the US by no more than 2%.

The cost competitiveness of these four economies has increased significantly compared to other economies in the region. Compared with the other 10 European economies in our index and Russia, the direct production cost structure of the UK and the Netherlands has improved significantly. Similarly, India and Indonesia have increased their cost competitiveness compared to the other five Asia Pacific economies in our index. Therefore, we have rated the UK, the Netherlands, India and Indonesia as “regional starsâ€.

The UK has become the lowest-cost economy in Western Europe, followed by Spain. According to our index, the competitiveness of the UK is about 5% higher than that of Belgium, compared with 6% in Poland, compared with 8% in France and 9% in Switzerland. The UK's flexible labor market makes it easier to adjust the amount of labor when the economic environment changes, which is the UK's main competitive advantage (see "British: Regional New Stars"). Therefore, the UK may be a good place to invest.

UK: Regional Rising Stars In June 2008, when India’s Tata Motors acquired Jaguar Land Rover from Ford for $2.3 billion, many people worried that another sign of the glorious industrial history of the UK would be transferred to Asia, and there were still Thousands of high-paying jobs. But then Jaguar Land Rover's three production sites in the UK quickly improved. Now, Jaguar Land Rover is investing heavily in expanding production. It is building a state-of-the-art, $840 million new plant in Woerhampton, England. Jaguar Land Rover will recruit talent for the first 1400 jobs in the plant in March. The plant will be used to produce new engines with high technology and low emissions. Jaguar Land Rover said it will add 1,700 jobs to its Solihull plant in the UK by 2015, which will produce the Jaguar XE premium sedan with a new advanced aluminum structure.

Other global automakers also take advantage of the UK's lowest cost economy in Western Europe. According to the Financial Times, since 2010, a number of auto companies have announced that their investment in the UK has reached 10 billion pounds (about 16.8 billion US dollars), including the expansion of Nissan, Honda and BMW Group's MINI series. British car production has increased by about 50% since 2009. The Financial Times predicts that by 2017, UK car production will increase by another one-third to 2 million. More than 80% of the cars made in the UK are exported, most of which are exported to other European economies.

Since the moderate increase in wages in the UK over the past decade has been largely offset by productivity gains, the UK's direct manufacturing cost structure is 10% higher than other leading Western European manufacturing exporters, according to the Boston Consulting Group's Global Manufacturing Cost Competitiveness Index. The competitive advantage of the UK compared to Eastern European economies such as Poland and the Czech Republic and Asian economies such as China has also improved.

As a result, various manufacturing companies, from toy trains to fashion, have relocated their production plants back to the UK. According to a recent survey by the British Manufacturing Consulting Service, 11% of small and medium-sized manufacturing companies in the UK have said that they have moved their production plants back to the UK in the past 12 months, and 22% said they will transfer their jobs abroad.

The UK's advantage lies not only in labor costs. The UK corporate tax rate is the lowest in Europe and has fallen from the current 28% to 20% before 2015, close to half of the US. The automotive industry in Midlands and Oxfordshire, the aviation industry in Bristol, England, and the high-tech manufacturing in East London and Warwickshire form a strong UK-based industry, including engineering and parts suppliers. Manufacturing ecosystem.

But the real advantage of the UK is the flexibility of the workforce. The Fraser Institute, a Canadian policy research institute, rated the UK's overall labor market as the highest of all economies in Western and Eastern Europe. The flexible labor market enables manufacturing companies in the UK to adjust their structure more quickly than other European economies. When the investment cycle resumes growth, the flexible labor market is more attractive to companies to establish factories and create jobs in the UK.

From 2004 to 2014, the Netherlands' productivity-adjusted labor costs have declined compared to the United States. Because during this time, the average annual growth rate of manufacturing wages in the Netherlands is only about 1.7%, while the average annual growth rate of productivity is about 2%. The cost of natural gas and electricity for industrial use in the Netherlands is 10%-30% lower than most European neighbors.

Manufacturing costs in India and Indonesia have changed more, with costs rising in some areas and falling in others. Although the average manufacturing wages of the two economies have more than doubled in the past decade, productivity gains and currency depreciation offset wage increases. From 2004 to 2014, the Indian rupee depreciated by 26% against the US dollar, while the Indonesian rupee depreciated by 20% against the US. The energy costs of the two countries have also increased relatively. From 2004 to 2014, natural gas prices in India increased by 6.5% annually, while natural gas prices in Indonesia rose by 5.2% annually, far less than the leading Asian manufacturing economies.

If India and Indonesia can improve their competitiveness, they can better use low labor costs and energy costs to increase exports of manufactured goods. Although Indonesia has the lowest direct production cost among the top 25 exporting countries in the world, it ranks 59th in terms of logistics efficiency, 114th in the Integrity Index, and lags behind the 120th in ease of business. In addition, Indonesia needs to improve its local supply chain to reduce its reliance on imported materials, parts and machinery. India's low-cost advantage has also been offset by the backward ranking of secondary factors, ranking 46th in logistics efficiency, 94th in the Integrity Index, and 134th in ease of doing business. (See "India: Staying Stable")

India: Staying stable If there is an industry that benefits the most from India's rising low-cost advantage, the most likely is the cotton textile and apparel industry. India is the world's second-largest cotton exporter and has a large and growing workforce. In addition, India's productivity-adjusted labor costs have barely increased over the past decade, making India attractive to the apparel industry, where labor costs account for nearly 30% of total costs. In contrast, labor costs in China's coastal provinces have almost tripled.

But India's apparel industry accounts for only 3% of global apparel trade, and there is no significant construction of cotton textile or garment factories in India. Instead, Indian cotton and yarn are still shipped to China, and then woven into fabrics at factories in China, Bangladesh, Cambodia and Vietnam.

The reasons for this indicate that India still needs to overcome certain difficulties in order to fully convert low-cost advantages into manufacturing investment and increased exports from various industries. In terms of direct production costs, our index shows that India's competitiveness relative to the US remained stable from 2004 to 2014. In Asia, India has the potential to become a regional star. Rapid productivity growth and currency depreciation offset the increase in Indian manufacturing wages. India’s electricity and natural gas costs have increased less since 2004 than other major Asian exporting economies.

But secondary factors other than direct production costs bring other risks and hidden costs, thereby weakening India's competitiveness. The inefficient nature of the Indian port has extended freight times. It usually takes six months in India to complete the regulatory procedures required to set up a new factory. India's labor regulations make it difficult and costly to manage labor in the off-season, which dispels the enthusiasm of companies to build large-scale, cost-effective factories in India. Although the government has determined that the electricity bill is low, in fact many Indian manufacturing companies have to pay much more electricity than other Asian economies. Because India has a shortage of electricity all year round, many factories must provide high-cost diesel generators.

Of course, Indian manufacturing also has optimistic aspects. India is building container terminals and highways, and the increase in electricity trading has reduced the cost of electricity in certain industries. In addition, India is building special economic zones, speeding up the approval of regulatory procedures and helping companies manage human resources. The Indian government has made greater efforts to improve India's position as a global manufacturing base.

But India wants to turn low-cost advantages into capital, first of all to reform labor, energy and investment regulations. If the new Indian government can complete these reforms, then India is likely to become the next manufacturing star in Asia.

Global Costs Manufacturing costs competitiveness in the United States and Mexico has increased significantly over the past decade compared to all other economies in our index. These two economies have maintained stable wages based on productivity and currency exchange rates or have improved competitiveness relative to other economies. The energy costs of these two economies are very competitive (see chart below).

The biggest factor affecting the cost of manufacturing in Mexico is the adjusted labor cost based on productivity. In 2000, the labor cost of manufacturing in Mexico was twice that of China. But since 2004, the wages of Chinese workers have almost doubled, while the wages of Mexican workers have only increased by 67%, if only 50% after the conversion of Mexico to the US dollar. Although the productivity growth rate is higher, Mexico's average labor cost adjusted for productivity is currently estimated to be 13% higher than China's. In addition, Mexico's electricity and natural gas costs are also very competitive, so Mexico's total manufacturing costs are estimated to be 5% lower than China's, 9% lower than the US and 10% lower than Poland. 11% lower than South Korea and 25% lower than Brazil (see "Mexico: Global Nova").

Mexico: Global stars more than a decade ago, Mexico's manufacturing development faced severe challenges. In the 1980s and 1990s, thousands of joint venture factories (maquiladora, located in Mexico, belonging to American companies) were established in the industrial zone on the US-Mexico border. Subsequently, China’s accession to the World Trade Organization revolutionized the global manufacturing economy. From clothing to automobiles, the investment and employment of the US-Mexico joint venture, which manufactures everything, has swarmed to China, where the number of workers is high and wages are extremely low.

Now, this situation seems to be reversed. Even in some industries where China has a monopoly position, foreign investment in Mexican factories has re-emerged. For example, from 2006 to 2013, Mexico’s exports of electronic products increased more than twice, reaching $78 billion. Asian companies such as Sharp, Sony and Samsung account for one-third of Mexico's electronics manufacturing investment, compared with about 8% a decade ago.

The Mexican consulting firm IQOM pointed out that in fact, Foxconn Technology Group, the largest investor in China's electronics manufacturing industry and Taiwan's electronics manufacturing giant, is the second largest exporter in Mexico, second only to General Motors. Foxconn said that the Foxconn plant in San Jerónimo, Chihuahua, Mexico, has 5,500 workers and exports 8 million personal computers a day. The factory is currently undergoing a massive expansion.

What is driving the recovery of Mexican manufacturing is the change in cost competitiveness. The Boston Consulting Group's global manufacturing cost competitiveness index shows that China's average direct production cost was 6% lower than Mexico's ten years ago, while Mexico is now estimated to be 4% lower than China. In fact, Mexico's manufacturing cost structure has the largest increase in all of our index's 25 economies.

The main reason is that labor costs in China have soared and productivity has not been able to offset the impact. In Mexico, the average manufacturing wage increase from 2004 to 2014 was 67% offset by productivity gains, and another 11% was offset by the depreciation of the Mexican peso against the US dollar. Mexico has also benefited from the decline in natural gas prices caused by US shale gas development. Since 2004, Mexico's industrial natural gas prices have fallen by 37%, giving Mexico an energy cost advantage over most other exporting economies.

In addition to cost, there are several factors that are also beneficial to Mexico. Mexico has signed free trade agreements with 44 economies (more than any other economy), including the North American Free Trade Agreement, which allows Mexican goods to enter the United States duty-free.

Mexicans have a strong professional ethic. Compared to the people of any other economy in the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Mexicans have more average annual working hours and fewer labor conflicts. Most Mexican manufacturing companies know how to eliminate security risks by reducing the violence caused by drug abuse, but they still need to be vigilant.

Mexico is experiencing rapid growth in many industrial industries such as transportation equipment, household appliances and computer hardware. Of the world's top auto parts manufacturing companies, 89 have factories in Mexico and 70 have assembly lines or production-related components in Mexico.

Mexican President Enrique Pena Nieto may further enhance Mexico's competitiveness by promoting infrastructure development, improving the investment climate and reducing energy costs. For example, the Mexican energy industry’s liberalization of the right to develop shale gas and offshore oil to private developers will increase Mexico’s energy cost competitiveness. This approach may strengthen Mexico's position as a global manufacturing star.

From 2004 to 2014, the manufacturing cost gap between the United States and other highly developed economies has widened dramatically. Currently, the average manufacturing cost in the United States is estimated to be 9% lower than in the UK, 11% lower than Japan, 21% lower than Germany, and 24% lower than France.在较大的å‘达出å£ç»æµŽä½“ä¸ï¼Œåªæœ‰éŸ©å›½çš„å¹³å‡åˆ¶é€ æˆæœ¬ä¸Žç¾Žå›½æŽ¥è¿‘,韩国的平å‡åˆ¶é€ æˆæœ¬ä»…高于美国2%。事实上,æ£å¦‚波士顿咨询公å¸åœ¨ä¹‹å‰çš„ç ”ç©¶ä¸è®¨è®ºåˆ°ï¼Œç¾Žå›½å·²ç»æˆä¸ºå‘è¾¾ç»æµŽä½“ä¸åˆ¶é€ 业æˆæœ¬æœ€ä½Žçš„ç»æµŽä½“。åŒæ—¶ï¼Œç¾Žå›½å®žçŽ°åˆ¶é€ 业æˆæœ¬å¤§è‡´ä¸Žä¸œæ¬§ç»æµŽä½“æŒå¹³ã€‚美国与ä¸å›½çš„åˆ¶é€ ä¸šæˆæœ¬å·®è·ä¹Ÿåœ¨å¿«é€Ÿç¼©å°ï¼Œå¦‚果这一趋势æŒç»10年,那么这个差è·å°†ä¼šåœ¨å年内消失。

劳动力是美国æ高竞争优势的关键。美国是å‘è¾¾ç»æµŽä½“ä¸åŠ³åŠ¨åŠ›å¸‚场是最çµæ´»çš„。在全çƒå‰25ä½åˆ¶é€ 业出å£å›½ä¸ï¼Œç¾Žå›½åœ¨â€œåŠ³åŠ¨åŠ›ç›‘管â€æ–¹é¢æŽ’å最å‰ï¼Œå·¥äººç”Ÿäº§çŽ‡ä¹Ÿæœ€é«˜ã€‚美国生产的很多产å“æ ¹æ®ç”Ÿäº§çŽ‡è°ƒæ•´åŽçš„劳动力æˆæœ¬ä¼°è®¡æ¯”西欧和日本低20%-54%。

美国获得巨大的能æºæˆæœ¬ä¼˜åŠ¿æ˜¯æœ€è¿‘的事情。虽然全çƒå·¥ä¸šç”¨å¤©ç„¶æ°”ä»·æ ¼éƒ½åœ¨æ高,但自2005年以æ¥ç”±äºŽç¾Žå›½æ£å¼å¼€å§‹é‡æ–°å¼€é‡‡åœ°ä¸‹é¡µå²©å¤©ç„¶æ°”资æºï¼Œç¾Žå›½çš„天然气æˆæœ¬å´ä¸‹é™50%。目å‰ï¼Œä¸å›½ã€æ³•å›½å’Œå¾·å›½çš„天然气æˆæœ¬å¯¹äºŽç¾Žå›½ä¸æ¢3å€ï¼Œæ—¥æœ¬çš„天然气æˆæœ¬ç”šè‡³æŽ¥è¿‘美国的4å€ã€‚由于页岩天然气还是化工产业ç‰äº§ä¸šçš„é‡è¦è¿›æ–™ï¼Œå› æ¤ä½Žæˆæœ¬çš„页岩天然气还有助于使美国的电价低于大部分其他主è¦å‡ºå£å›½ã€‚这对钢é“和玻璃ç‰èƒ½æºå¯†é›†æ–°äº§ä¸šæ¥è®²å°±æœ‰å·¨å¤§çš„æˆæœ¬ä¼˜åŠ¿ã€‚天然气æˆæœ¬ä»…å 美国平å‡åˆ¶é€ æˆæœ¬çš„2%,而电力æˆæœ¬ä»…å 1%。但在大部分其他主è¦å‡ºå£å›½ä¸ï¼Œå¤©ç„¶æ°”æˆæœ¬å å¹³å‡åˆ¶é€ æˆæœ¬5%-8%,而电力æˆæœ¬å 2%-5%。

由于美国天然气储é‡å¹¿æ³›åˆ†å¸ƒï¼Œä»·æ ¼é¢„计将在未æ¥å‡ åå¹´ä¿æŒåœ¨æ¯1000一立方英尺4-5美元以内。å¦å¤–,由于还需è¦ä¸€æ®µæ—¶é—´å…¶ä»–ç»æµŽä½“æ‰æŽŒæ¡å¼€é‡‡é¡µå²©å¤©ç„¶æ°”的能力或者美国æ‰å‡ºå£å›½å†…的页岩天然气,所以至少在未æ¥5-10年北美ä»ç„¶å æ®ä¸»è¦æˆæœ¬ä¼˜åŠ¿ã€‚

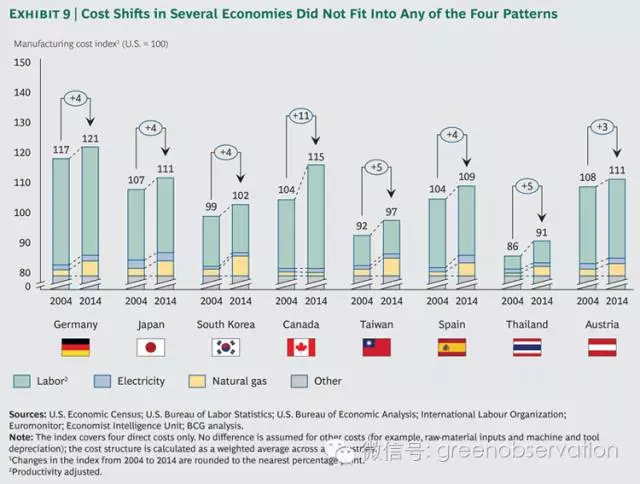

ä¹Ÿæœ‰å‡ ä¸ªé¢†å…ˆçš„åˆ¶é€ ä¸šå‡ºå£ç»æµŽä½“ä¸å±žäºŽä¸Šè¿°å››ç§æ¨¡å¼ï¼Œå› 为它们的æˆæœ¬ç»“æž„çš„å˜åŒ–没有呈现上述明显模å¼ï¼ˆè§ä¸‹å›¾ï¼‰ã€‚虽然德国和日本相对英国ã€ç¾Žå›½å’Œè·å…°çš„优势也有所å‡å¼±ï¼Œä½†å¾·å›½å’Œæ—¥æœ¬ç›¸å¯¹ä¸å›½ã€å·´è¥¿å’Œå¾ˆå¤šæ¬§æ´²ç»æµŽä½“则ä¿æŒäº†ä¼˜åŠ¿æˆ–者优势增强。å¦å¤–,韩国和å°æ¹¾ç›¸å¯¹ç¾Žå›½ã€å°åº¦å’Œå°åº¦å°¼è¥¿äºšçš„æˆæœ¬ç«žäº‰åŠ›å‡å¼±ï¼Œä½†è¿™ä¸¤ä¸ªç»æµŽä½“在ä¸å›½ã€ä¿„ç½—æ–¯ã€æ³°å›½ã€æ³¢å…°å’Œæ·å…‹å…±å’Œå›½ç‰æ–°å…´å¸‚场å æ®é‡è¦ä»½é¢ï¼Œå¹¶ä¸”相对巴西ã€æ¾³å¤§åˆ©äºšå’Œæ³•å›½çš„优势大幅增强。虽然自2004年以æ¥ï¼ŒåŠ 拿大相对美国的æˆæœ¬ç«žäº‰åŠ›å‡å¼±11%ï¼Œä½†åŠ æ‹¿å¤§çš„ä¼˜åŠ¿å¹¶æ²¡æœ‰ç»§ç»å‰Šå¼±ï¼Œå› 为它也得益于天然气æˆæœ¬çš„下é™ã€‚

åå¹´å‰ï¼Œå¾ˆå°‘人预测到å‘达地区和å‘展ä¸åœ°åŒºåŒæ—¶å‘生的工资和能æºæˆæœ¬æŒç»è€Œåˆå·¨å¤§çš„改å˜ã€‚但在å˜å¹»èŽ«æµ‹çš„å…¨çƒç»æµŽä¸ï¼Œæœ‰ç†ç”±ç›¸ä¿¡è¿™ç§å˜åŒ–å°†æŒç»ä¸‹åŽ»å¹¶ä¸”å„个ç»æµŽä½“的相对æˆæœ¬ç«žäº‰åŠ›å°†å‡ºäºŽåŠ¨æ€å˜åŒ–ä¸ã€‚æ— è®ºæ˜¯ä¼ä¸šè¿˜æ˜¯æ”¿ç–制定者都ä¸èƒ½æ»¡è¶³äºŽçŽ°æœ‰çš„竞争优势。

æˆæœ¬ç«žäº‰åŠ›è½åŽçš„ç»æµŽä½“需è¦é©¬ä¸Šé‡‡å–行动é¿å…åˆ¶é€ ä¸šç«žäº‰åŠ›è¿›ä¸€æ¥å‡å¼±ï¼Œè€Œé‚£äº›é¢†å…ˆçš„ç»æµŽä½“也ä¸å¯ä»¥å›ºæ¥è‡ªå°ã€‚

æˆæœ¬ç«žäº‰åŠ›çš„å˜åŒ–对全çƒè¿è¥çš„åˆ¶é€ ä¼ä¸šæœ‰æ·±åˆ»å¯å‘。这些å¯å‘包括:

æ高生产率。由于过去å‘è¾¾ç»æµŽä½“å’Œå‘展ä¸ç»æµŽä½“的巨大工资差è·åœ¨ç¼©å°ï¼Œæ高æ¯ä¸ªå·¥äººçš„生产率æˆä¸ºèŽ·å¾—å…¨çƒåˆ¶é€ 业竞争力的é‡è¦å› ç´ ã€‚ä¼ä¸šåº”该é‡æ–°è¯„ä¼°æ高自动化和其他å¯ä»¥å¤§å¹…æ高生产率的措施对æˆæœ¬å¸¦æ¥çš„好处。

æ€è€ƒæ•´ä½“æˆæœ¬ã€‚虽然劳动力æˆæœ¬å’Œèƒ½æºæˆæœ¬ç‰ç›´æŽ¥ç”Ÿäº§æˆæœ¬ä»æžå¤§åœ°å½±å“åˆ¶é€ ä¸šçš„é€‰å€å†³ç–ï¼Œä½†å……åˆ†è€ƒè™‘å…¶ä»–å› ç´ ä¹Ÿéžå¸¸é‡è¦ã€‚例如,物æµã€ä¼ä¸šæ•ˆçŽ‡çš„éšœç¢ä»¥åŠç®¡ç†è¶Šæ¥è¶Šé•¿çš„å…¨çƒä¾›åº”链的éšå½¢æˆæœ¬å’Œé£Žé™©éƒ½å¯èƒ½æŠµæ¶ˆåŠ³åŠ¨åŠ›æˆæœ¬å’Œæ±‡çŽ‡æ–¹é¢çš„优势。考虑缩çŸä¾›åº”链的éšæ€§æˆæœ¬ä¼˜åŠ¿ä¹Ÿå¾ˆé‡è¦ï¼Œä¾‹å¦‚:进入市场速度更快ã€çµæ´»æ€§æ›´é«˜å’Œæ ¹æ®ç‰¹å®šå¸‚场定制产å“的能力更强。

考虑更广泛供应链的æ„义。虽然目å‰æŸäº›ç»æµŽä½“直接生产æˆæœ¬ç›¸å¯¹è¾ƒä½Žï¼Œä½†ä¼ä¸šè¿˜å¿…须考虑零件和æ料的需求。也许ä¼ä¸šçŽ°åœ¨è¿˜æ²¡æœ‰æ‰¾åˆ°å¯é 的本地供应商。但在æŸäº›æƒ…况下,价值链æ–裂å¯èƒ½å¯¼è‡´ç‰©æµæˆæœ¬æ高或者é¢å¤–的关税或其他æˆæœ¬ã€‚ä¼ä¸šè¦ä»Žç«¯åˆ°ç«¯ä¾›åº”链的角度æ¥ç†è§£å®ƒä»¬å½¢æˆç½‘络的决ç–,从而é¿å…æ„外风险。

完善商业环境。ä¼ä¸šåº”该与业务所在ç»æµŽä½“的相关监管部门和政ç–制定者ä¿æŒæ²Ÿé€šï¼Œè¯´æœå®ƒä»¬å‡å°‘ä¼ä¸šç»è¥çš„困难并采å–å‘展基础设施和å‡å°‘è…è´¥ç‰æŽªæ–½æ高ç»æµŽä½“çš„å…¨çƒç«žäº‰åŠ›ã€‚

é‡æ–°è¯„ä¼°ä¼ä¸šå•†ä¸šæ¨¡å¼ã€‚想用åŒæ ·çš„工艺和原æ料就“é¢é¢ä¿±åˆ°â€çš„模å¼è‚¯å®šä¸æ˜¯æœ€ä½³çš„选择,ä¼ä¸šåº”该充分利用本地生产的优势,考虑对产å“或商业模å¼è¿›è¡Œè°ƒæ•´ä»¥æ›´å¥½åœ°æ»¡è¶³æœ¬åœ°éœ€æ±‚。例如,使用本地供应的ä¸åŒæ料或者在资本设备æˆæœ¬ä½ŽäºŽåŠ³åŠ¨åŠ›æˆæœ¬æ—¶åˆ©ç”¨æœºå™¨äººå’Œ3D打å°ç‰åˆ¶é€ 技术更为åˆç†ã€‚相比在其他地方使用åŒæ ·çš„æ料和工艺,作出类似的改å˜å°†ä½¿ä¼ä¸šæ›´å¥½åœ°æ»¡è¶³æœ¬åœ°å¸‚场的需求。

调整全çƒç½‘络。ä¼ä¸šæ˜¯æ—¶å€™é‡æ–°è¯„ä¼°ä¼ä¸šçš„å…¨çƒç”Ÿäº§è¿è¥å’Œé‡‡è´ç½‘络,并使它们与全çƒåˆ¶é€ ç»æµŽè½¬ç§»ç›¸é€‚应。明确全çƒå„个地区目å‰å’Œæœªæ¥çš„产å“需求,在全çƒé€‰æ‹©æœ€ä½³çš„商å“å’ŒæœåŠ¡ä¾›åº”商。

对很多ä¼ä¸šæ¥è®²ï¼Œå…¨çƒåˆ¶é€ ç»æµŽè½¬ç§»è¦æ±‚它们用新æ€ç»´æ´žå¯Ÿä¸–界,而ä¸æ˜¯æŠŠä¸–界仅仅划分为低æˆæœ¬å’Œé«˜æˆæœ¬ä¸¤ä¸ªæ–¹é¢ã€‚åˆ¶é€ ä¸šæŠ•èµ„å’Œé‡‡è´çš„决ç–åº”è¯¥æ›´å¤šåœ°æ ¹æ®å¯¹å„个地区竞争力的最新的ã€å‡†ç¡®çš„ç†è§£ã€‚

那些用过时的æˆæœ¬ç«žäº‰åŠ›ç†å¿µå‘展生产能力的ä¼ä¸šï¼Œé‚£äº›æ— 法把长期趋势è¿ç”¨åˆ°è‡ªèº«åœºæ™¯ä¸çš„ä¼ä¸šï¼Œå¾ˆå¯èƒ½åœ¨æœªæ¥äºŒä¸‰åå¹´å¤„äºŽåŠ£åŠ¿ï¼›è€Œé‚£äº›æ ¹æ®å…¨çƒåˆ¶é€ ç»æµŽè½¬ç§»è°ƒæ•´ä¸šåŠ¡çš„ä¼ä¸šï¼Œé‚£äº›çµæ´»åº”对ç»æµŽè½¬ç§»çš„ä¼ä¸šï¼Œåˆ™å¾ˆå¯èƒ½æˆä¸ºèµ¢å®¶ã€‚

Amazing global manufacturing cost changes

Abstract Introduction: In the past three decades, the US economy has been in a good stage, and the roughly divergent worldview has influenced the investment and purchasing decisions of manufacturing companies. Most of Latin America, Eastern Europe and Asia are considered low-cost regions, while the United States, Western Europe and Japan are considered high-cost regions. but...

Introduction: In the past three decades, the US economy has been in a good stage, and the roughly divergent worldview has influenced the investment and purchasing decisions of manufacturing companies. Most of Latin America, Eastern Europe and Asia are considered low-cost regions, while the United States, Western Europe and Japan are considered high-cost regions. But this worldview seems to be out of date now.